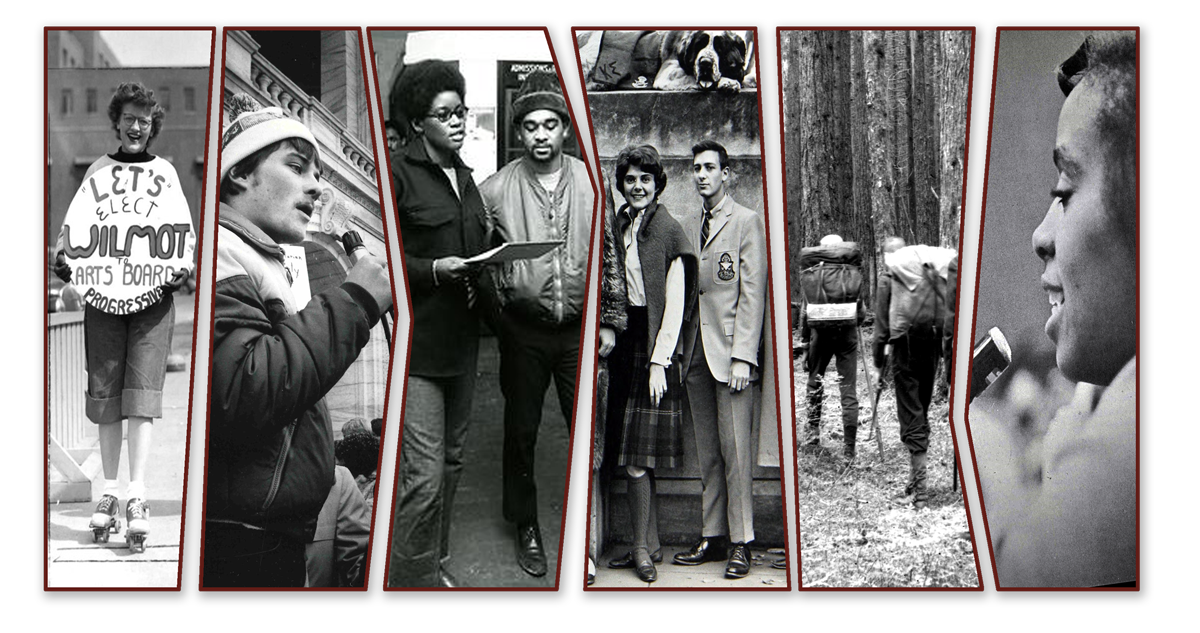

Calling To Question

150 years ago, the University of Minnesota’s College of Science, Literature, and the Arts was founded. Throughout that century and a half, the thread of liberal education has been a consistent one at the University—even if the name of the College, the departments within it, and the student population have changed immensely.

Many stories—personal, political, educational, or otherwise have come from what is now known as the College of Liberal Arts. The flashpoints highlighted in this gallery illuminate moments where questioning plays a significant role. Liberal education permits and encourages a questioning to achieve a high standard of critical thinking. Over the years, questioning has been used by students, faculty, and community members as a method to push the College and liberal education beyond its bounds in order to create a more equitable learning environment and society.

"The power in learning, I suppose, is in asking the right questions, not in the answers. The answers have always been wrong.” -Fred Lukerman, CLA Dean, 1978-1989

Acknowledgement

The University of Minnesota—Twin Cities is built within the traditional homelands of the Daḳota people. Minnesota comes from the Daḳota name for this region, Mni Sota Maḳoce—the land where the waters reflect the skies.Circle of Indigenous Nations quoting Iyekiyapiwiƞ Darlene St. Clair, Bdewakaƞtuƞwaƞ Daḳota

Liberal Education

Liberal education has been the cornerstone of the College of Liberal Arts, even before it was called such. Nevertheless, throughout the past 150 years, liberal education at the University of Minnesota has experienced many changes and challenges. Sciences have removed themselves from the college, prompting discussions about who desires or needs a liberal education and what questions a liberal education can answer. Legislators have challenged the use of the word “liberal,” presuming political intentions, which has politicized certain types of knowledge. See the changes that liberal education at the University of Minnesota has weathered to better understand the events in the College of Liberal Arts, and your own relationship to those changes.

In This Section:

Founding Documents

In 1868, 17 years after the founding of the University of Minnesota, the College of Science, Literature, and the Arts (SLA) was established alongside the College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts. Later, SLA would become the College of Liberal Arts. Despite not always being represented in the name, liberal education has been a key tenet of learning at the University of Minnesota from its beginnings.

The University is a land-grant university, per the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862. This act established universities across the country with the purpose of promoting “the liberal and practice education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.”

Reorganization

In 1960, a series of letters from the Departments of Geology and Mineralogy, Zoology, and Botany addressed to SLA Dean E.W. McDiarmid and President J.L. Morrill initiated changes in the College. These letters requested transference from SLA to the Institute of Technology or a separate Institute of Sciences, partially motivated by budgetary concerns.

Letter addressed to CLA Dean E.W. McDiarmid from faculty in the Botany Department requesting their removal from SLA into an Institute of Technology. Dated June 30, 1960.

Letter addressed to CLA Dean E.W. McDiarmid from the Chairman of the Geology and Mineralogy Department requesting the department's removal from SLA into an Institute of Technology. Dated April 27, 1960.

Letter addressed to CLA Dean E.W. McDiarmid from faculty of the Geology and Mineralogy Department requesting the department's removal from SLA into an Institute of Technology. Date June 2, 1960.

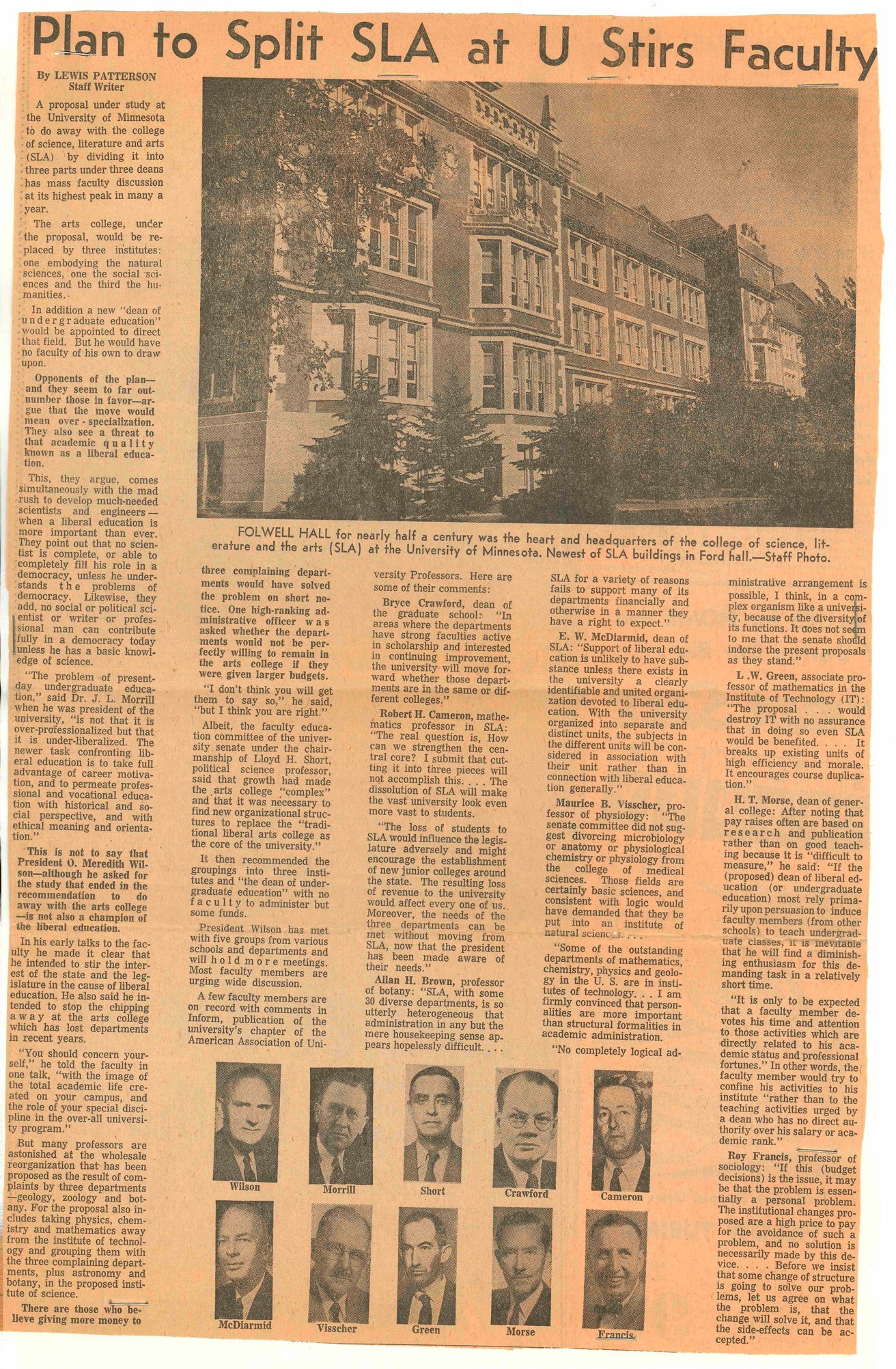

Press

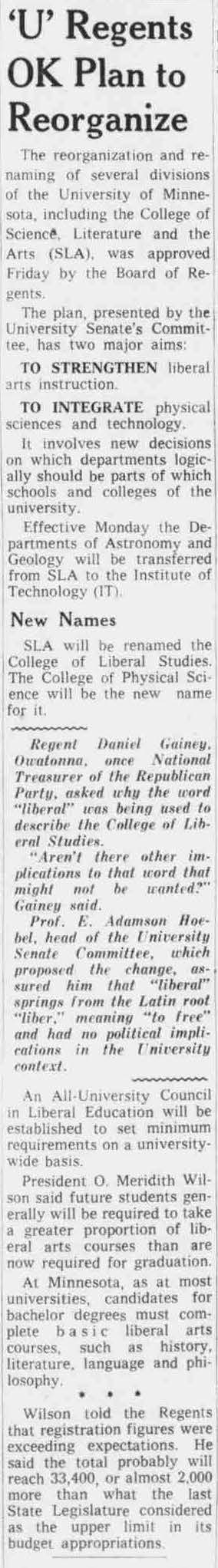

The removal of these sciences from the College of Science, Literature, and the Arts sparked a reorganization effort that resulted in a renaming of the college. The College of Science, Literature, and the Arts became the College of Liberal Studies and was shortly thereafter renamed the College of Liberal Arts. Alongside a renaming, debates arose about the university’s responsibility to liberal education and the word “liberal” itself.

Regent Daniel Gainey, Owatonna, once National Treasurer of the Republican Party, asked why the word "liberal" was being used to describe the College of Liberal Studies. "Aren’t there other implications of that word that might not be wanted?" Gainey asked. Prof. E. Adamson Hoebel, head of the University Senate Committee, which proposed the change, assured him that liberal springs from the Latin root liber, meaning to free and had no political implications in the University context.

Confidential draft of a paper under discussion in the Senate Committee on Education – October 26, 1961.

Headline from the Minnesota Daily reads: Plan to Split SLA at U Stirs Faculty. Dated October 9, 1961.

The reorganization and renaming of several divisions of the University of Minnesota, including the College of Science, Literature, and the Arts (SLA), was approved Friday by the Board of Regents.

The plan presented by the University Senate’s Committee, has two major aims: To strengthen liberal arts instruction. To integrate physical sciences and technology

Effective Monday the Departments of Astronomy and Geology will be transferred from SLA to the Institute of Technology (IT).

New Names

SLA will be renamed the College of Liberal Studies. The College of Physical Science will be the new name for it.

Regent Daniel Gainey, Owatonna, once National Treasurer of the Republican Party, asked why the word “liberal” was being used to describe the College of Liberal Studies.

“Aren’t’ there other implications to that word that might not be wanted?”Prof. E. Adamson Hoebel, head of the University Senate Committee, which proposed the change, answered him that “liberal” springs from the Latin root “liber,” meaning “to free” and had no political implications in the University context.

My colleague, Prof. Hoebel, may have succeeded in lulling regential scruples but at the same time he repeated a wide-spread and long-standing misconception about the use of the adjective “liberal” in western education

Historically, “liberal arts” was never used to suggest that these are the studies which can or should “free” men from the bondage of superstition, fear, intolerance and related attitudes which are regularly by-products of ignorance. Parenthetically, the aim of “freeing” or “liberalizing” (Latin “libero”) a student’s outlook is of course a laudable one, and is to be hoped that the encounter between enlightened teachers, such as Prof. Hoebel, and conscientious students always does work in that direction.

Actually, though, the “artes liberals” of early medieval educational theory and practice simply carried on that much older Graeco-Roman idea that these are studies appropriate to “freemen” or citizens, as opposed to slaves. There is admittedly an element here of snobbery and class-consciousness, for which the ancient world had to pay dearly.

But few will quarrel with the basic concept that the education of future leaders in all branches of a society should be broad and flexible and should avoid narrow concentration on a particular occupation or profession.

Free Speech

Throughout the past century and a half, conflicts over free speech have been and continue to be a recurring issue faced by faculty and students in the College of Liberal Arts. Often, comedy or the arts have been mobilized to critique the college or another power structure. Free speech also means the freedom to not say things and it also does not mean students or community members cannot hold those in power accountable. When considering the ever-present principle of free speech, consider: what faculty and students have the privilege to take advantage of free speech, and which ones took risks with no such protections in place?

In This Section:

Junior Exhibitions

Almost a decade after the College of Science, Literature, and the Arts was founded, the classes of 1877 from both SLA and the College of Agriculture participated in a Junior Exhibition, highlighting their talents.

The sophomores were tasked with printing the programs. They simultaneously printed satiric programs (called “Rams”) that mocked the juniors in the exhibitions. This shocked faculty and resulted in the expulsion of some students.

The following year, despite attempts to prevent these "Rams" from appearing, the Class of 1879 created at least three different Rams mocking the Class of 1878. This resulted in Junior Exhibitions being cancelled until 1881, when the satirical Rams continued to be produced.

Junior Exhibition Program, 1876.

Junior Exhibition Program, Class of 1877.

Junior Exhibition Program, 1877.

Junior Exhibition Program, Class of 1878.

Tenure

In times of conflict, free thought, and subsequently, liberal education, is sometimes threatened. What is regarded as “educational” is then pushed beyond the bounds previously understood. Often, but not always, this results in a more equitable educational experience.

In 1917, professor of political science William A. Schaper was dismissed from the faculty on charges of disloyalty to the United States for his alleged “rabid pro-German” views during World War I. Despite efforts of students and other faculty for Schaper’s case to be reopened, it would take over 20 years for the Regents to rescind the decision of September 13, 1917, and make amends to Schaper.

Schaper was reimbursed for his salary during the 1917-1918 year and was asked to return to the University. Though he declined to return, he became professor emeritus. This decision also generated principles of academic freedom, setting forth a foundation for faculty tenure policies that are in effect today at the University of Minnesota.

Excerpt from Board of Regents meeting minutes, September 13, 1917

Excerpt from Board of Regents meeting minutes, January 28, 1938.

Theatre

In the 1939-1940 academic year, the theatre department and University Theatre planned a production of Porgy, which required an all Black cast. However, protests from the Council of Negro Students stopped the production of the play, likely due to the stereotypical portrayal of African Americans. The play was replaced with Susan and God.

Correspondence between Chairman Rarig and Ruth Gage Thompson. An excerpt from an article about the production change from Porgy to Susan and God.

Forrest O. Wiggins

Dr. Forrest O. Wiggins was hired in 1946 as an instructor of philosophy, making him the first African American to be given a regular full time teaching appointment at the University, however, he was later dismissed before receiving tenure status. During his time, Wiggins developed four new courses in the Department of Philosophy and was heralded by both students and other philosophy faculty as someone who stimulated thought and academic engagement.

Many of Wiggins' Jeffersonian Democratic beliefs and statements both challenged and created discomfort within the University and the legislature. The philosophy department and students around the university protested Wiggins' dismissal. Although newspapers and the University abruptly brushed off claims of racial discrimination, the administration would not release the details that led to Wiggins' firing on December 11, 1951.

"On the eve of my retirement, I can say sincerely that if I can feel I have left behind me a group of students who felt a fraction of the admiration and respect for me that these students expressed toward Dr. Wiggins, I shall retire a happy man." -Dr. George Conger, philosophy

Skol, February 1952.

Student Report published by Student Action Committee.

Mulford Q. Sibley

Dr. Mulford Q. Sibley, professor of Political Science, had similarly "radical" ideas, like Forrest Wiggins. His tenure at the University overlapped with Wiggins' and they even debated at one point.

Sibley's time at the University lasted much longer than Wiggins’ and did not end in dismissal. Instead, Sibley's "radical" teachings were considered by the University administration and the press as opportunities to reflect upon academic freedom. Despite this, fears around Communism ran rampant at the University.

Anti-Communist pamphlet, 1964.

Letter from Professor Sibley, 1963.

Charlie Hebdo

Free thought also entails the risk of being critiqued and held accountable. In 2015, this poster advertising a CLA-sponsored event depicted an image of the prophet Muhammed--following the murder of 12 Charlie Hebdo magazine staff members earlier that year.

The poster sparked outcry from 260 Muslim students, staff members, and others not affiliated with the university. Though faculty and the College of Liberal Arts Dean, John Coleman, agreed that the poster was protected speech, The Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action also disavowed the image depicted on the poster.

Ultimately, reprinting the image on event posters alienated many Muslim students and was considered blasphemous and insulting, particularly because it came from those with “positional power” at the University.

“We can’t allow those who are hurt to stop the conversation; and we can never stop paying attention to their pain, because that’s part of the conversation as well.” -Riv-Ellen Prell, organizer of the event

"Can One Laugh At Everything? Satire and Free Speech After Charlie" event poster

Note: The parodic image of Muhammad was not reprinted on this version of the poster. The curator did not feel its replication was necessary in order to discuss the matter of free speech.

New Avenues of Thought

When students or faculty in the liberal arts cannot find answers to the questions they ask, opportunities for new avenues of thinking can arise. This has been the case from the early days of the College of Liberal Arts and continues to this day. There was a swell of new departments and programs in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the founding of Afro-American Studies, American Indian Studies, Chicano Studies, and Women’s Studies. This process of expanding thought and creation of new theoretical frameworks allows the College of Liberal Arts to be a more equitable learning environment.

In This Section:

Journalism

A course in journalism, which had been supported by faculty, including those in rhetoric and English, was rejected by the Board of Regents in 1907. Dismayed by the "hog slop" that was in the Minnesota Daily, Regent Dr. John G. Moore remarked that, "The people on the Daily should take courses in English and rhetoric until they know how to write."

In February of 1909, SLA junior Carl Anton Anderson initiated the Voluntary Course in Journalism at the University of Minnesota.

Anderson reserved a room in the Library (later Burton Hall) and hung up posters and advertised the 10-week, no credit course. He tactfully avoided antagonizing the Regents for fear of expulsion. Anderson visited people in the industry throughout the Twin Cities, including William J. Murphy, owner of the Minneapolis Tribune. He sought endorsements for the course and recruited speakers. Journalists from across the area spoke on different subjects in journalism over the length of the course.

Journalism cont.

"Not to have journalism here is one of the most absurd things I know of... Newspapers exert two-thirds of the influence of all American literature today. Why then, should we not have the men who write our newspapers, trained to exert the best influence?" -Dr. Burton

It was not until 1917 that a journalism curriculum was officially offered at the University of Minnesota. In 1918, William J. Murphy bequeathed $350,000 from his estate to establish instruction in journalism. The Department of Journalism was founded four years later.

Anderson felt that "a course in journalism is an awakener. It bursts the bounds of the young person, man or woman. The trained reporter will be forced to see things, and have experiences that others may never have...Curiosity will burst the fetters that bind most youths. Regardless of whether he becomes a journalist or not, he will never be satisfied until he has ventured over the earth and seen for himself what is going on."

Evolution & Religion

In 1927, local church leaders led the proposal of the “Anti-evolution Bill” in the State Legislature. Prior to this, Reverend W.B. Riley tried to host an anti-evolution lecture at the University was uninvited from speaking. Students and faculty successfully helped defeat the bill.

In a tax-supported institution, the topic of teaching religion was tentatively approached. Though religious subjects were taught in other CLA departments, the establishment of a religious studies department prompted disagreements across faculty. Religious studies began as an interdepartmental major, but not as an organized program. This changed in 1972 when the program was finally approved and the first faculty member in religious studies was hired.

Christian Fundamentals in School and Church, 1926.

Committee Report, 1954.

Unsigned student pro-evolution petition, n.d.

Article on W.B. Riley and Dr. Burton, n.d.

The Teaching of Evolution, 1930.

Update, pages 4-5, 1976.

Febuary 14, 1976 Report.

African American Studies

The Morril Hall takeover in 1969 was a critical moment in the history of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota. This protest and movement are examples of students and the Twin Cities African American community calling the role of the College into question. The importance of it can been seen in the ripple effects it created in CLA in the years and decades to come.

An example of the effects the Morrill Hall Takeover had on everyday CLA courses was seen in a humanities course called, "Institutional Racism in America," a class intended for people not necessarily in the African American studies department. A student-published source of news and commentary was generated from this class entitled Free Amerika.

In 2006 a summit was organized to reunite the students who were involved in the Morrill Hall Takeover.

Free Amerika, April 24, 1970.

Free Amerika, May 4, 1970.

Reunion News, 2005.

American Indian Studies

In May 1969, a committee recommended the creation of the American Indian Studies Program, only one day after the All-College Council approved the African American Studies Department.

While the students and activists from the American Indian Movement pushing for this department used a variety of tactics to reach their goal, they also credited the Afro-American Action Committee for the acceleration of this process. From the beginning of the idea of the department, languages were of high importance.

Rose Barstow and Carolynn Schommer taught students Ojibwe and Dakota languages, respectively. They were two of several Native people, mostly women, who were part of this groundbreaking language program in American Indian Studies.

Though not considered “professors,” these “teaching specialists” in Native languages were the key to success for the language program. Their funding was never certain, so their position in the college was always a precarious one.

Committee meeting minutes, 1980.

Minnesota Daily, October 11, 1993.

Department of American Indian Studies brochure, 1970.

Preliminary draft of a proposal for a program of American Indian Studies

Under the Axe

When newer programs arise, they are often small and sometimes comprised of marginalized faculty and students. Bureaucratic and budgetary forces threatened these departments in the early 1980s when funding from the legislature to the University slowed. CLA underwent the process of “Retrenchment and Reallocation.” During this time, budget cuts were made in the college and the easiest targets for these budget cuts were smaller, newer departments despite their budgets making up only a small and insignificant percentage of CLA’s overall budget.

In this section:

Chicano Studies

The Chicano Studies program was founded through action from Twin Cities area Chicanos and the Latin Liberation Front in 1972. Founded during university retrenchment, Chicano Studies struggled for establishment. Once Chicano Studies found roots at the University, the learning extended beyond campus, despite the constant threat of downsizing and disestablishment.

A letter to the Vice-President from 'Concerned Chicanos and Friends,' 1971.

Minnesota Daily, January 14, 1982.

Department of Chicano Studies Newsletter, Spring 2006.

"U Chicano Students Deny Threat Charges" press release

Humanities

Newly formed and smaller departments, mostly in the Humanities Program, suffered hiring freezes and the reduction of funds. These otherwise minor cutbacks had placed major constraints on these small departments. Women’s Studies, South and Southwest Asian Studies, American Indian Studies, and Chicano Studies even faced dissolution.

Articles on cutbacks. Women’s Studies teach-in poster, 1981.

RIGS

In 2014, students from the University of Minnesota organized Whose Diversity?, a collective of graduate and undergraduate students comprising people from marginalized and underrepresented communities at the University. They identified injustices at the University of Minnesota, despite claims by the administration of a diverse student body.

The group’s demands and actions were not specific to CLA. Yet, many of them were students in CLA and their actions led to the formation of the Race, Indigeneity, Gender and Sexuality Initiative (RIGS). The founding departments were Asian American Studies, African American and African Studies, American Studies, American Indian Studies, Chicano and Latino Studies, and Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies.

Liberal Arts in Conflict

Periods of unrest or wartime in the United States result in shifts in University education—for students and the college’s administration. During the Cold War, the United States utilized liberal arts education to their advantage; at the same time, the Red Scare put faculty and students under increased surveillance. During the Vietnam War students from the entire University participated in direct action, pushing the boundaries of what liberal education can mean to students and faculty.

In this section:

Cold War

During The Cold War, smaller area studies saw a boost in their funding through the National Defense Education Act, which passed the U.S. Senate in 1958. The NDEA allocated financial aid to students and to programs that were considered to “be in the national interest” of the United States. While this act included the sciences and mathematics, it also financially supported education in certain modern languages that would create citizens ready to contribute to national defense.

Copy of S. 3187 or National Defense Education Act, 1958.

NDEA foreign language proposals, 1959.

Area Studies and Study Abroad pamphlets.

Various public conference flyers.

Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, student and faculty dissent rocked college campuses across the country. The University of Minnesota was no exception. Students engaged in conscientious objection, backed by many CLA faculty. Protests erupted across campus, and teach-ins were used as supplements or replacements for regularly scheduled classes.

University education is often imagined to take place, if not in a classroom or lab, in an orderly fashion. Students that embrace a liberal education see opportunities for learning outside of these conditions. This has never been more apparent than in times of social and political unrest.

Ad Hoc faculty committee resolution in support of Vietnam protests.

Ally with Campus Workers statement.

University of Minnesota schedual for Vietnam Moratorium.

A letter to the faculty from Dean E.W. Ziebarth regarding the National Crisis Course in the Social Sciences.

These “nontraditional” methods of learning left some students, parents, and community members questioning the usefulness and efficiency of the College of Liberal Arts. The core of protests often began in the liberal arts because students are taught to question. The answer to conflicts also usually are found within the liberal arts.

University of Minnesota Report to Parents with information about National War Protests.

Correspondence between Dean E.W. Ziebarth and Mr. & Mrs. Charles Smith

University of Minnesota Teach Out Activities

Vietname Commemement Pledge of Support.

Acknowledgements

“Calling to Question: 150 Years of Liberal Arts Education at the University of Minnesota” was on display at the University of Minnesota Elmer L. Andersen Library March 4 - June 12, 2019.

Curator

Noah Barth, Graduate Student, Heritage Studies and Public History

Physical Exhibit Design

Darren Terpstra, Exhibit Design/Project Specialist, University of Minnesota Libraries

Digital Exhibit

Simon Whitney, Web Developer, College of Liberal Arts

150th Archives Committee

Erica Giorgi, Alumni Relations, College of Liberal Arts

Kaylee Highstrom, Sr. Advancement Officer and Campaign Director, College of Liberal Arts

Megan Mehl, Director of Alumni Experiences and College Events, College of Liberal Arts

Scott Meyer, Chief Marketing Officer, College of Liberal Arts

Erik Moore, Head, University Archives & Co-Director, University Digital Conservancy

Special thanks to

College of Liberal Arts Faculty, Student Board, and Ambassadors

These documents are available in alternative formats upon request. Direct requests to the Office of Institutional Advancement at clanews@umn.edu or 612-625-5031.